‘I’m no longer ashamed of crying’

A volunteer in Russia’s underground support network for Ukrainian refugees tells his story

“I want to have this on me forever. It’s part of me, and I don’t know if I’ll ever forget it,” says Vyacheslav Korshunov, showing me a child’s drawing of a black cat, with the sun and a blue cloud in the sky above and green grass growing beneath its feet.

I woke up on the morning of 24 February 2022 and saw the news. I had a terrible feeling it was all over. I had lost Russia, my motherland, for ever and there was no future.

Chat threads for volunteers sprung up, and requests for help were published there. The coordinator would say things like: a family from the Donetsk region is on its way and needs somewhere to stay overnight in Bryansk. I would answer and start looking for somewhere through people I knew. Many people were sympathetic. Sometimes you had to meet people or bring them food, clothes or suitcases.

But we — my friends and I, that is — still thought our region was OK, because we read news from other parts of the country, where things were totally bleak. People were being tortured and imprisoned. We were only threatened with having our genitals clamped in a vice.

There was a constant flow, and everyone had their own story, their own terrible story. Those first few days I met refugees, I would just go and cry in the evenings. It’s impossible to ignore that your country is killing unarmed people in your name.

It turns out they had to stay in our shelter for almost two weeks. The husband had had a stroke shortly beforehand, and had an epileptic seizure on his way into Russia. They needed to stay where they were for him to recover. His wife cooked us potato pies and helped us however she could, and the husband would show me videos. There was one rock band he really loved and he showed me them performing. I asked a friend to print the group’s merch to give it to them when they were leaving.

Those six months I spent meeting refugees, living with them, sharing their joy and pain and listening to their stories, really changed me. I’m no longer ashamed of crying. People have had terrible things happen to them, at the whim of one crazy old man, and they have lost everything. Some have lived in their basements, others have lost loved ones, but they’ve all lost their homes.

Как хотят наказывать за «отрицание геноцида советского народа»

«Новая-Европа» разбирается в новом законопроекте, жертвами которого могут стать журналисты, историки и учителя

Джей Ди Вэнс едет на Южный Кавказ

Каковы интересы Америки и какие новые геополитические смыслы обретает регион?

Маменькин сынок

История «сибирского потрошителя» Александра Спесивцева

Разведка в Абу-Даби

Кто такой Игорь Костюков — начальник ГРУ, возглавивший российскую делегацию на переговорах по Украине

Друзьям — деньги, остальным — закон

Кто получает путинские гранты: от больницы РПЦ до антивоенных активистов

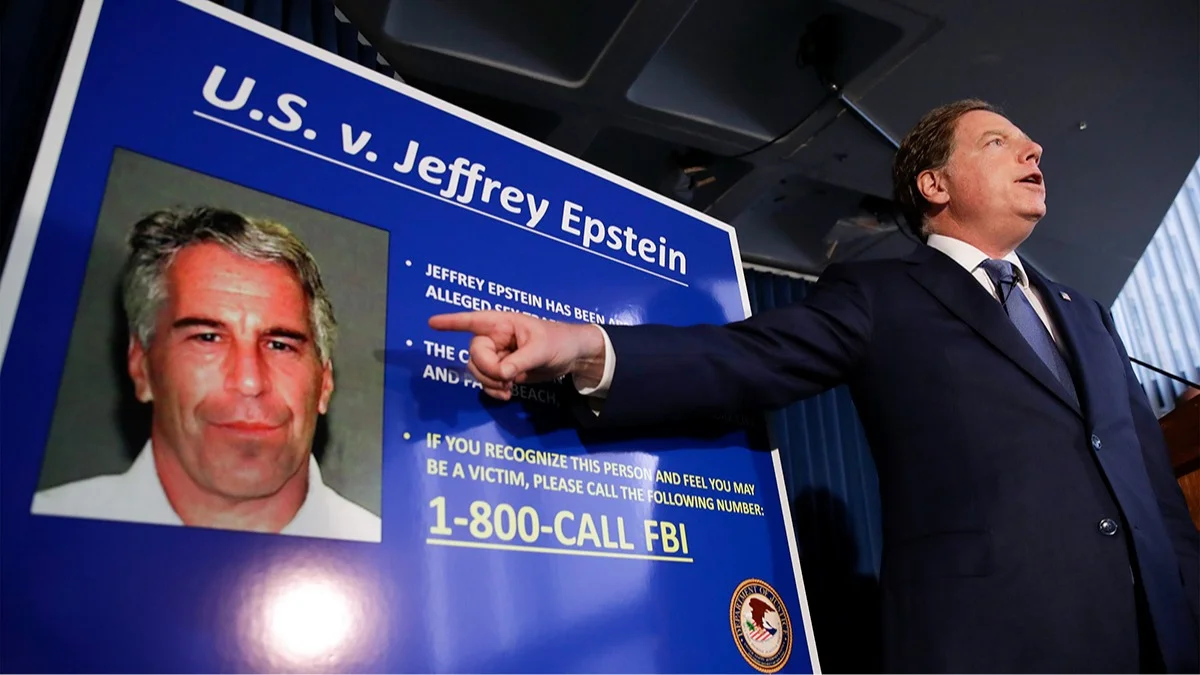

Три миллиона файлов по делу Эпштейна

Трамп и другие контакты: что удалось обнаружить в новом и, возможно, последнем крупном массиве документов?

Поймай меня, если сможешь

«Марти Великолепный» с Тимоти Шаламе — один из лучших фильмов сезона, рассказывающий историю об игроке в пинг-понг как криминально-авантюрную сагу

«Отношение к ним в Европе жестче, чем в первый год войны»

Что сейчас происходит с российскими дезертирами?

Что известно о ПНИ Прокопьевска, где из-за вспышки гриппа умерли девять человек

Сотрудники там жаловались на условия содержания пациентов: холод, испорченную еду и отсутствие лекарств