Surviving the flood

How war overtook and irreversibly changed the lives of one family in the Ukrainian town of Oleshky

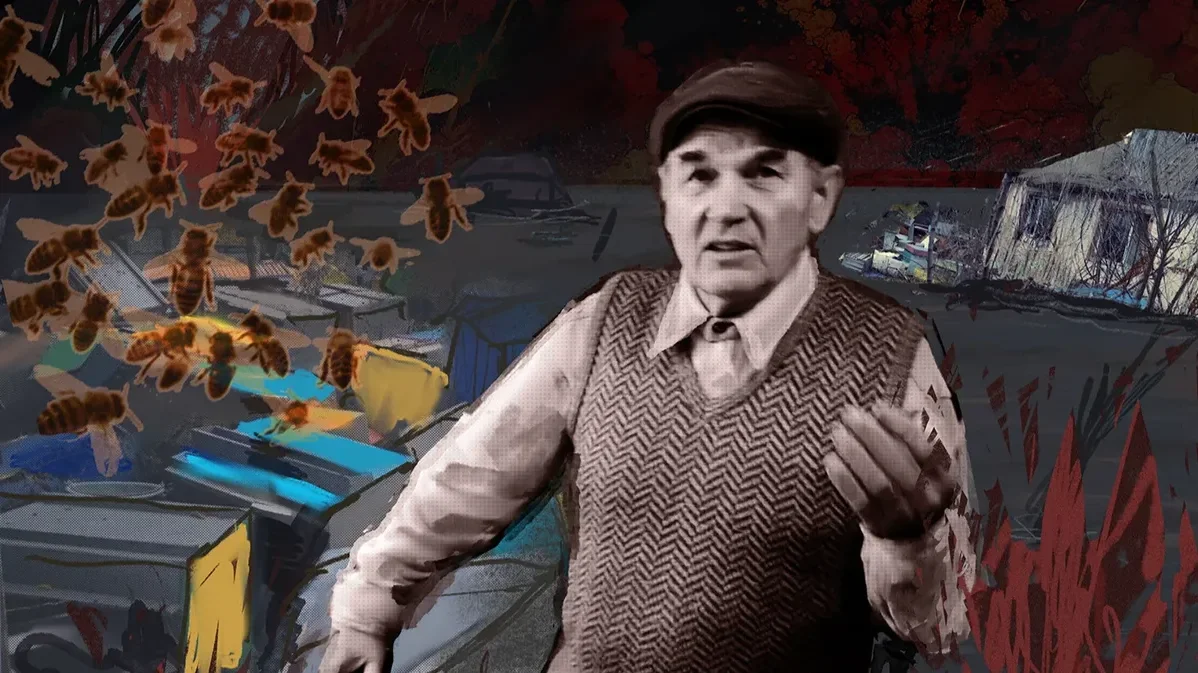

Oleshky native Mykola Stepanskyi, 74, was a professional beekeeper with his own honey farm until the so-called “Russian world” burst into his life and destroyed everything he lived for. His son was taken prisoner and tortured, then his daughter was killed in shelling. Finally, all his bees drowned when Oleshky was flooded by the collapse of the Kakhovka dam in June.

Stepanskyi’s grandson Slava, a paramedic in the local ambulance service, received a call that morning reporting dozens of injured people on the bridge: Russians and Ukrainians, soldiers and civilians. The paramedics had no idea who the injured were, Slava says, recalling seeing only severed limbs and numerous corpses.

“There were stories of people getting their children back from the Russians for a certain sum,” says Stepanskyi. “We were prepared to buy back our son as long as he was still alive, but nobody even mentioned money.”

One woman and her 12-year-old son particularly stuck in Oleh’s memory. They had been put in a cell either because she was the wife of a Ukrainian soldier or because her husband had passed on information to the Ukrainian army — nobody knew for sure.

Mykola says that anyone released from prison still remained under observation. “The men who were in the same cell as Oleh told him ‘Oleh, hide, otherwise they’ll bring you back. They don’t let anyone out of their clutches just like that.’” After his release, Oleh hid out at his family’s dacha, or with friends.

“First we were told that our daughter’s death was caused by Ukrainian shelling,” Mykola said. “But we heard where the firing was coming from. There was a tank not far away, firing randomly at houses.”

“But no, not a single person left, so great was the hatred towards those who brought sorrow to our homes, to our country,” says Mykola.

“I saw videos later on local channels of Russians sitting in trees, and the corpses of their soldiers floating down the Dnipro towards the sea. People said that many of the soldiers drowned, as many as a thousand. It shows that the Russian leadership not only doesn’t care about the civilian population, it doesn’t even care about its own soldiers — it is absolutely merciless.”

“I don’t know where her husband was, but for some reason she was alone with her children during the occupation. When the water began rising, she tried to climb up into the attic with her two babies, but she slipped and fell back into the water with them. They all drowned.”

“The border guards asked where our children were, but we didn’t tell them that our daughter had been killed by one of their shells. We said that they had stayed at home,” Mykola recalls.

“They say that time heals, but it doesn’t heal at all. Not a day has gone by when my wife hasn’t cried for our murdered daughter. Not a single day!”

My enemy’s enemy

How Ukrainians and Russia’s ethnic minority groups are making common cause in opposing Russian imperialism

Cold case

The Ukrainian Holocaust survivor who froze to death at home in Kyiv amid power cuts in the depths of winter

Cold war

Kyiv residents are enduring days without power as Russian attacks and freezing winter temperatures put their lives at risk

Scraping the barrel

The Kremlin is facing a massive budget deficit due to the low cost of Russian crude oil

Beyond the Urals

How the authorities in Chelyabinsk are floundering as the war in Ukraine draws ever closer

Family feud

Could Anna Stepanova’s anti-war activism see her property in Russia be confiscated and handed to her pro-Putin cousin?

Cries for help

How a Kazakh psychologist inadvertently launched a new social model built on women supporting women

Deliverance

How one Ukrainian soldier is finally free after spending six-and-a-half years as a Russian prisoner of war

Watch your steppe

Five new films worth searching out from Russia’s regions and republics