Picking your battles

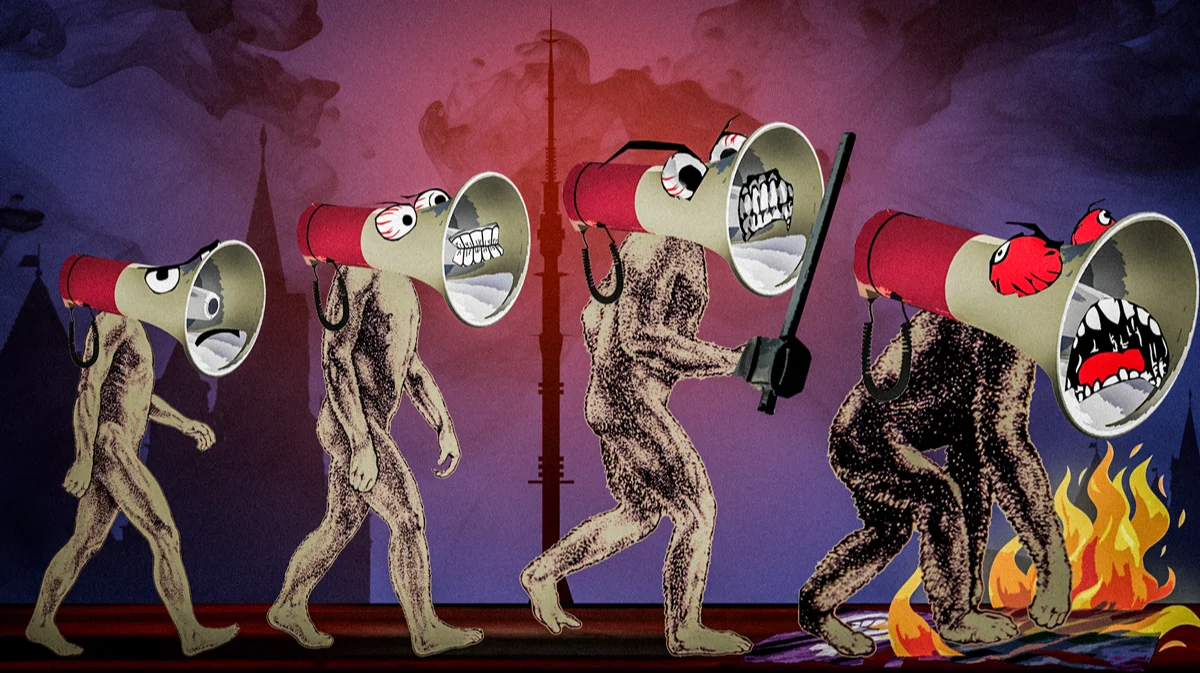

Novaya Europe analysed almost 40,000 protests to see how Russia’s war in Ukraine has changed civil society

Why don’t Russians protest? Politicians, political scientists and sociologists have all asked the question since the war began. But while the Kremlin has a well-oiled repressive machine in place for dealing with anti-war feeling in the country, there are still frequent instances of civic action — from miners’ strikes to animal rights rallies.

Over the past three years, political parties and other movements have only organised 15% of protests.

1280 раз сообщалось о коммунальных авариях в январе — в два раза больше, чем год назад

Почему ЧП так много и как выжить в мороз?

Дом, в который пришла война

Спецпроект «Новой-Европа» о преступности ветеранов «СВО»

Краткая история ненависти

«Новая-Европа» изучила пять миллионов публикаций в провластных СМИ и составила хронологию травли оппозиции, мигрантов и приверженцев «нетрадиционных ценностей»

О чем спорили боты

Топ-10 новостей 2025 года, на которые активнее всего реагировали прокремлевские аккаунты в соцсетях

Война на карте России

2025 год стал рекордным по количеству атак беспилотников по российским регионам. В среднем падает или попадает в цель 11 дронов в день

Российские регионы один за другим вводят запрет на «склонение женщин к абортам»

Где уже действует законопроект, а где его только обсуждают. Карта

Больше четырех тысяч аварий произошли на российских энергообъектах в 2025 году

Причина каждого десятого отключения света – атака ВСУ, остальные – износ инфраструктуры. На ремонт денег нет

Плетут Путину — 3

В новом созыве Европарламента стало больше депутатов, голосующих так, как выгодно Кремлю. Но этого всё еще не достаточно, чтобы изменить отношение ЕС к войне в Украине

Первая гибридная

За последние месяцы в Европе произошло не менее 74 воздушных инцидентов, в которых подозревают Россию. Пострадали почти два десятка стран